TCHRD and PEN Tibetan honor imprisoned Tibetan writers: Event graced by Kirti Rinpoche and Chang Ping

On 15 November 2014, the Tibetan Centre for Human Rights and Democracy (TCHRD) and Tibetan Writers Abroad PEN centre (Tibetan PEN) organized an event to highlight the fate of Tibetan writers imprisoned by Chinese authorities on PEN International’s Day of the Imprisoned Writer.

15 November 2014 is the 33rd anniversary of the PEN International’s Day of the Imprisoned Writer. The 150 PEN Writers Associations throughout the world commemorate the day by organizing events, including seminars, to highlight the fate of imprisoned writers. PEN Writers Associations will officially send letters to the presidents and embassies of these countries, appealing for the immediate release of the imprisoned writers.

Organized by TCHRD and Tibetan PEN on 15 November 2014 at Peace Hall of Kirti Monastery in Dharamsala, India, the event saw the release of two publications by TCHRD. The first, a collection of essays by imprisoned Tibetan writers inside Tibet in Chinese translation titled “Who are the Real Splittists?” and the second, a report on China’s forced resettlement of Tibetan nomads. The goal of the first book is to circumvent Chinese censorship and allow Tibetan writers to speak directly to the Chinese-speaking public. Among the Chinese speaking public, information regarding Tibet and Tibetans are distorted by the Chinese government’s censorship policy, especially since the 2008 Tibetan uprising. TCHRD believes that the best way to counter this misconception is by giving the Chinese-speaking public an opportunity to hear directly from Tibetan writers. The book is also a tribute to the courage and sacrifice of the Tibetan writers who have suffered torture, beatings and lengthy prison terms for exercising their basic right to expression. The second book, a special report in English on the Internally Displaced Persons in Tibet, is aimed at highlighting China’s forced relocation and resettlement of Tibetan nomads and farmers. Since 2013, almost two million Tibetans, predominantly nomads, have been displaced from their ancestral lands to make way for Chinese ‘development’ in Tibet. Resettled in concrete houses in urban areas, displaced Tibetans suffer from innumerable problems such as the loss of their traditional economic livelihood and cultural dislocation.

The speakers at the event discussed critical human rights issues faced by Tibetans inside Tibet, including the lack of freedom of expression and the series of important resolutions passed on imprisoned Tibetan writers by the PEN International. To express support and solidarity with imprisoned Tibetan writers, the PEN Tibetan released two books, Labrang Jigmey Gyatso “Diaries of Hardship and Struggle” and Jado Rinchen Sangpo’s “The Power of Justice” in Tibetan language. In the first book, Jigme Gyatso sheds light on the current situation of Tibet, based on his personal diaries and interviews with journalists, but the book was banned from publication in Tibet for having “negative political content.” He was recently sentenced after years of incommunicado detention to five years in prison. Jado Rinchen is suffering from severe physical and mental disability after he was brutally beaten and tortured in prison. He was arrested and imprisoned for writing a book that documented the real situation of Tibet under the Chinese rule. The Chinese police seized most of his compositions, but the remaining few that survived, including his important work “The Unforgettable Red Fire” could not be printed and distributed inside Tibet. The book released at the event under revised title, “The Power of Justice”.

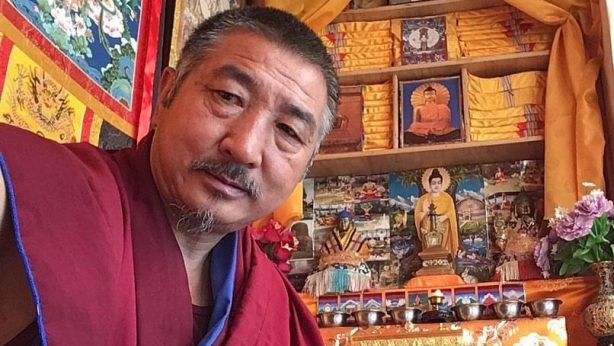

His Eminence Kirti Rinpoche was the chief guest at the event. He spoke on His Eminence Kirti Rinpoche talks about the importance of Tibetan language and literature in reflecting the reality of the situation in Tibet, adding that the Tibetans hold no grudges against the Chinese people but that they are against the ‘you die, I live’ Chinese policy which seeks to annihilate the existence of Tibetan culture and language.

Noted Chinese writer, journalist and columnist Chang Ping was the special guest. Chang Ping is a prominent journalist in China before his exile in Germany in 2011. He is the former news director of Southern Weekend, and former deputy editor of Southern Metropolis Weekly, based in Guangzhou. Chang had dared to go where many fear to tread, such as writing about politically sensitive topics including human rights, freedom and democracy. In 2011, Chang was barred from visiting and working for iSun Affairs in Hong Kong. In 2008, a year in which he was expelled from his newspaper job at Southern Metropolis Weekly, Chang wrote a column on Tibet headlined “Tibet: Nationalist Sentiment and the Truth” which sought to question the official Chinese narrative on the March incident in Lhasa.

Chang presented a prepared speech titled “How Many Words Have Been Spoken?” In an eloquent and passionate speech, Chang called the event a way to “amplify the voices of ‘those who have spoken’.” TCHRD presents here a bilingual presentation of Chang Ping’s Speech, “How Many Words Have Been Spoken?” at the Day of the Imprisoned Writers event organized by TCHRD and Tibetan PEN.

有多少话被说出来

How Many Words Have Been Spoken?

~ Chang Ping

尊敬的会议主办者、尊敬的藏人作家、尊敬的各位来宾,大家好!

Greetings to our gracious hosts and to the Tibetan writers and guests in attendance!

受邀见证一本藏人作家的汉语译文著作的出版,我感到非常荣幸。它把我带回到二十多年前的岁月。那时我是一个迷恋文学和语言哲学的大学生。那时中国的大学生大多热爱文学和哲学。那时中国热心时事的成年人大多在从事写作。街边一片梧桐树叶随风坠落,会从三个诗人头上飘过,而且每个人会为这片树叶写三首诗。

It is my honor to be invited to this book launch for an anthology of Tibetan writers that has been translated into Chinese. This volume transports me back to my youthful days, over 20 years ago. I was a university student deeply immersed in the world of literature and linguistic philosophy. In those days, the majority of Chinese university students were passionate about literature and philosophy. A great number of people were engaged in the art of writing. There’s a joke: When the wind blows on the roadside sycamore tree, any falling leaf would be carried over the heads of at least three poets walking by and each poet would go on to compose a different poem for the leaf.

这不只是嘲笑诗人太多的笑话。那时中国社会正在酝酿一场巨大的变革,文学被历史选中成为主要的载体。“文革”时期的地下诗歌,“文革”之后的伤痕文学、寻根文学、报告文学、现代小说、后现代诗潮,像一波又一波滚烫的岩浆,炙烤着一个从僵冷中复苏的社会。文学被选择,不仅因为直接谈论政治改革仍然属于禁区,而且受西方文学、诗学、语言学和哲学理论的启发,很多中国人意识到语言革命的必要性。

This is not just a joke about there being too many poets in the streets. It actually reflects the social revolution that was brewing in China and the role of literature as its primary catalyst. A tidal wave of radical literary styles flooded our minds, including the underground poetry of the Cultural Revolution, the Scar literature movement (shanghen), the Root-seeking movement (xungen), first-hand reportage, modernist fiction, and postmodern poetry. Like waves of hot lava melting away layers of ice, these literary movements brought Chinese society out of cold storage and back to life. Literature was the chosen outlet of expression because the overt discussion of politics was still banned. With the end of the Cultural Revolution, people were also exposed to the literature and critical theories of the West. Inspired by the influx of new knowledge, many Chinese people recognized the urgent need for a revitalization of language itself.

思想的死亡,从语言的枷锁开始,也以语言的僵化结束。1942年5月,毛泽东发表了著名的《在延安文艺座谈会上的讲话》。从那以后,中共政权对文学艺术进行更加直接的干扰和管制。反右期间,用“洗澡”、“脱裤子”等粗鄙言语对知识分子进行羞辱,强迫他们进行灵魂的自我改造。文革期间,中国的文学艺术只剩下八个样板戏。唯一具有生气的语言就是毛主席语录,仿佛一个醉汉站在八亿不敢动弹的人头上狂欢。

The death of intellectual life in China began and ended with language control. In May 1942, Chairman Mao Zedong gave his famous speech at the Yan’an Forum on Literature and Art, which launched the Chinese Communist Party’s direct control over the production of art and literature. During the Anti-Rightist Campaign (1957-59), the party humiliated writers and intellectuals with crudely worded slogans such as “Take a bath!” or “Take off your pants!” The goal was to shame people into changing their thinking. By the time of the Cultural Revolution (1966-76), China’s literary scene had been reduced to just eight “model theater” scripts that were sanctioned for production. Sadly, the only work with any glimmer of vitality was “Quotations from Chairman Mao Zedong.” The scenario calls to mind the image of a mad drunkard rejoicing in triumph while standing on the heads of 800 million people too afraid to move.

作为对于文革期间语言简单枯燥的反叛,朦胧诗以意向丰富的语言表达,开启了以文学质疑政治的新时代。诗歌发展到八十年代中期,全中国流派众多,“非非主义”、“他们”派、“撒娇”派……他们的一个共同特点是,试图从语言本体上进行表达的革命。他们含混不清地,喊出了很多寻找、回归、抽离、背叛语言的口号,也进行了各种维度的语言实验。这场实验生产了很多无病呻吟的文字垃圾,但是它对于语言表达与内在生命关系的探索,仍然值得肯定。

In an open revolt against the simplified and dessicated language of the Cultural Revolution, the “Misty poetry movement” (menglong shi) used colorful and emotive language to usher in a new era of political critique in literature. By the mid-1980s, Chinese poetry had spawned a range of countercultural movements across the nation, including the “No-no movement,” (feifei zhuyi), the “Them school” (tamen pai), and the “Cute school” (sajiao pai). What unified these diverse strands was their common effort to revolutionize the expressive power of language. There was no shared message, but rather an eclectic mix of ideas and agendas that encompassed a collective soul-searching, a recovery of traditional ideals, and a spirit of rebellion. They experimented with language at all different levels and coined new concepts and slogans. The results that emerged were often incoherent, overly sentimental, or just plain literary garbage. Yet as a whole, these movements injected the Chinese language with new expressive abilities that reflected an exploration of the inner psyche. Thus they are worthy of recognition.

就在这个时候,我读到了很多藏族诗人的作品,受到极大的震动。这些作品有发表在《诗刊》、《西藏文学》等出版刊物上的,也有发表油印的地下刊物上的。有些是用汉语写作的,有些是从藏语翻译过来的。我惊喜地发现,汉族诗人们痛苦挣扎地想要摆脱的各种语言桎梏,藏族诗人那里本来就没有。1949年以后的中国政治对藏族作家当然也有污染,但是也许因为言语的陌生和隔离,也许因为高原的坚硬的风可以吹尽尘埃,高原赤裸的阳光可以杀死病菌,相对与汉族诗人的纠缠,藏族诗人的作品干净、灵性、开阔和深邃。对于我们习以为常、一晃而过的词语,藏族诗人们仿佛会暂停下来,庄严地呈现。如同我昨天深夜经过漫漫长路来到达兰萨拉时,看到满天明亮的繁星。

It was at this very moment that I began reading Tibetan poetry. I was stunned by what I discovered. These works were being published in major journals such as Poetry or The Literature of Tibet, as well as underground publications that skirted the censors. Some Tibetan writers were writing in Chinese while others had their works translated into Chinese. I was struck by the realization that Tibetan writers did not share the same desperate struggle as Chinese writers trying to break free from a dead and shackled Chinese language. Of course, the post-1949 state policies had a detrimental impact on Tibetan writers. Yet Tibetan writers lived at a certain distance from the Chinese language. They also lived on the high altitude grasslands, with powerful winds and fresh sunlight that could heal the body and cleanse the environment. Compared to the convoluted works of the Chinese writers, Tibetan poets were composing verses that were full of clarity, openness, spirituality, and profundity. These works drew attention to the words and phrases that we normally take for granted in daily life, the ones that pass us by in a flash without us noticing their simple beauty or power. It is like the epiphany I experienced last night when I was walking along the path to Dharamsala and suddenly noticed the sky above me, full of magnificent twinkling stars.

毫无疑问,藏族作家对于世界文学、包括汉语言文学的发展,作出了巨大的贡献。当时西藏题材在汉语写作中是一种时尚,但是大多作品神秘化和他者化,触及藏人真实生活和文化的作品并不多见。如果那场语言革命能继续下去,也许更多藏族作家的作品可以让更多中国人看见。

There’s no doubt that Tibetan writers have made a major contribution to world literature, including the development of Chinese literature. At the time, it was a fad among Chinese writers to take up Tibetan themes. Yet the vast majority of these works were exoticized misrepresentations of the cultural other. One would rarely see writings that offered a realistic depiction of Tibetan life or culture. If the era of experimental writing had continued longer, we might have seen more Tibetan writers sharing their stories with a Chinese audience.

一场大悲剧让这些以文学为载体的社会革命嘎然而止。那就是1989年的六四天安门屠杀。在这场屠杀之前,是很多汉人根本没有留意到的对藏人抗议者的屠杀。那一年的鲜血一直流到现在。那一年的冤魂至今仍在哭泣。那一年种下的恶树,今天已经开花结果。

Unfortunately, a devastating tragedy brought all this literary experimentation and social transformation to an abrupt end – the 1989 Tiananmen massacre. Many Chinese had no idea that a massacre of Tibetan protestors had already taken place before the Tiananmen incident. The blood flows to this day and the cries of the dead are still heard. An evil tree was planted that year and today this tree has come to bear its ugly fruit.

那一年,苏联解体,东欧巨变,冷战成为历史。中国人付出生命的代价,催开了一时令世界无比鲜艳的自由之花。然而,中国民主运动却冷战结束而被世界抛弃。政治对抗结束了,沟通和对话也许可以创造一个新世界,然而随之带来的却是全球资本的勾结和狂欢。中国政府是资本全球化最大受益者,这使得它有足够的力量来打压和孤立异议人士。

That year, the Soviet Union disintegrated and Eastern Europe was transformed. The Cold War became another chapter of history. The Chinese people had paid with their lives in vain, only to scatter the bright blossoms of freedom they had briefly enjoyed. Ironically, with the end of the Cold War, the Chinese democracy movement was abandoned by the world. As old political conflicts died down, there was an opportunity for greater dialogue and the construction of a new world order. Yet what followed instead was the rampant and frenzied spread of global capitalism. The Chinese state reaped the most profits as the nation embraced global capital; it also provided them with the power they needed to suppress and isolate the dissidents.

中共从苏东事变及其他颜色革命中总结的教训之一,就是要加强言论管制。大批知识精英被迫出走,流亡海外,国内高校的思想讨论淡出课堂,时事沙龙不见踪影,电影电视严格审查。报纸可以放开市场,但是政治报道严防死守。互联网为普通民众带来了发言机会,但是无处不在的长城防火墙和网络阅评员让它成为管制助手。

The Chinese Communist state learned an important lesson from the revolutions in the former Soviet Union as well as other “Color revolutions” around the world. They learned the necessity of controlling free speech. Many intellectuals were forced to leave the country to live in exile. Inside China, intellectual debate was eradicated from the institutions of higher education. Discussion forums dedicated to current events disappeared without a trace. TV shows and movies were heavily censored. Newspapers were allowed on the market, but political reports were strictly forbidden at all costs. The Internet offered some opportunities for ordinary people to voice themselves, yet the omnipresence of the “Great Firewall of China” and Internet censors has turned the web into just another tool of state control.

文学革命烟消云散,曾经才华闪烁的作家开始为市场写作,在出版社的包装下版税滚滚,不亦乐乎。先锋艺术家模仿了西方的政治波谱,还没有在中国扎稳脚跟就被西方艺术资本哄抬,不少人成了千万富翁,作品却只会为资本而重复。那些为了真相和真理而写作的作家,则被投入监牢。

The experimental and revolutionary trends in literature faded away as if they never existed. The most talented writers turned towards the demands of the marketplace. Packaged and branded by the mainstream publishers, they amassed their wealth in royalties. Avant-garde artists adopted the whole spectrum of political stances popular in the West, playing into the desires of Western art collectors and dealers. Before these artists could even establish a career in China, their works were getting sold for exorbitant sums in the Western art markets. Many of these artists became millionaires and joined the social elite. Yet their works are only valued as high-end commodities. On the other hand, the writers and artists who are still committed to addressing the actual realities of Chinese life are getting thrown behind bars.

中国政府一直试图告诉科学家和作家、艺术家,只要你们不碰政治敏感话题,专心做好科研,画好画,写好小说就可以了,为什么专业成就和西方社会差距那么大呢?他们不明白的是,人的思想和想象力是一个整体。政治上被压制,也就意味着所有方面都不自由。一个花瓣中毒枯萎了,整个花朵都将死去。

The Chinese authorities keep assuring the nation’s scientists, writers, and artists that they can do anything they want as long as they don’t touch any politically sensitive issues. As long as you put your energy into producing good research, painting good pictures, and writing good books, you will be successful. Yet it is plain for all to see that China lags far behind the Western world in both scientific and creative achievement. Why is this so? China’s leaders fail to grasp the holistic nature of human thought and creativity. It is impossible to stifle political debate without stifling all other forms of communication and learning. One poisoned petal will lead to the death of the whole flower.

我在中国大陆长大,目前居住在德国。我也经常被问到在海外进行汉语写作的问题,我总是想到从罗马尼亚移民德国的诺贝尔获奖作家赫塔•缪勒(Herta Müller)的一段话,对于语言是存在的家园等说法,她质问道: “纳粹对犹太大屠杀之后,保罗•策兰(一位用德语写作的犹太诗人)必须要面对自己的母语德语也是自己母亲的刽子手的语言这样的事实”,而又”有多少伊朗人至今仍会因为一句波斯话被投入监狱,有多少中国人、古巴人、朝鲜人、伊拉克人在自己的母语中无法有片刻在家的感觉”?她引用乔治•塞姆朗(Jorge Semprun)的话说:”家园,不是语言,而是被说出的话。”

I was born and raised in Mainland China but I now live in Germany. I’m often asked about the experience of writing in Chinese while living abroad. I’m always reminded of Herta Muller, the Nobel Prize Laureate who moved to Germany from Romania. When she was asked about the connection of language to a sense of home, she replied, “Paul Celan (an acclaimed Jewish poet who wrote in German) had to face the fact that his mother tongue was the same language spoken by his mother’s executioner.” She continued, “How many Iranians would be jailed for speaking Persian, and how many Chinese, Cubans, North Koreans and Iraqis speak their own languages yet feel like aliens in their own homelands?” She then quoted the words of Spanish writer Jorge Semprun, “Language itself does not constitute the homeland, but rather the words that are spoken.”

在场的很多作家朋友都和我一样,流亡在中国大陆之外用汉语写作、用藏语写作、用维吾尔语写作,用在那一片土地上生长出来的语言写作,烟波江上,乡关何处?那就是我们能说出的话。有多少话被说出来,就有多少家园的感觉。

Many of the writers here today are like me. We live outside Mainland China, but we write in Chinese, Tibetan, and Uighur. We write in the languages of our homelands, where we were raised. Where’s our home? It lies in the words that we speak. How many words have been spoken? That shall determine our emotional connection to home.

而那些因为写作而深陷囹圄的作家,他们在监牢里也许没有纸笔和电脑,没有说话的自由。但是,所幸他们曾经说过。他们曾经比别人说得更多,这些多说的话语将伴随着他们的终身,他们永远比别人拥有更多的家园。今天,我们将他们这些“说出的话”广为传播,就会让更多背井离乡者拥有家园。

For those who have been incarcerated for daring to write, they may not have pens, paper, or computers to write with. They have no freedom of speech whatsoever yet they have spoken loudly. They have spoken more than anybody else and their words will follow them for life. They will always be forever closer to home for having told their stories. Today, we will amplify the voices of “those who have spoken.” We will distribute their writings near and far and bring a sense of home to all those living in exile.

谢谢大家!

Thank you everyone.

Note: Click here to download TCHRD’s special report on the right of the internally displaced in Tibet

TCHRD’s Chinese language publication, “Who are the Real Splittists?” is available in hard copies. Write to us at office@tchrd.org for a copy.