Former Tibetan social activist serving 15 years’ sentence dead after less than 6 years in prison

According to reliable information received by the Tibetan Centre for Human Rights and Democracy (TCHRD), a Tibetan political prisoner serving a 15-year prison sentence died yesterday afternoon on 5 December. He was less than six years into his prison term in Chushur Prison near Lhasa city. His death confirms criticisms from human rights groups that torture and inhumane treatment is common in Chinese prisons in Tibet.

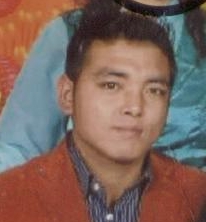

Tenzin Choedak, also known as Tenchoe, died just two days after he was released to his family by prison authorities. He died at Mentsekhang, the traditional Tibetan medical institute in Lhasa city, hours after his family admitted him there. Tenzin Choedak had previously worked for a European NGO affiliated to the Red Cross.

Early in November, as Tenchoe’s condition deteriorated prison authorities took him to three different hospitals for treatment. After the doctors gave up hope of saving Tenchoe, he was released to his family. He died two days later despite his family’s efforts to save him.

Tenchoe is not the first Tibetan to die in detention. Earlier this year in March, another Tibetan political prisoner Goshul Lobsang died months after prison officials released him to his family when his medical condition worsened beyond treatment in Machu (Ch: Maqu) County in in Kanlho (Ch: Gannan) Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Gansu Province. Goshul Lobsang suffered severe beatings and torture including pain-inducing injections in police detention.

Tenchoe used to work as a social activist for a foreign NGO affiliated to the Red Cross before his imprisonment. The Lhasa City Public Security Bureau (PSB) detained him in April 2008 on the charge that he acted as one of the ringleaders for the March 2008 protest in Lhasa City. Sources tell TCHRD that during police detention and interrogation, Tenchoe was severely beaten and tortured. During interrogation, the police focused much of their attention on his father, Mr. Khedup, who had participated in political activities in Tibet for many years until he was compelled to flee Tibet for exile in India in 1993. The interrogators insisted that Tenchoe was working on the instigation of his father. The Intermediate People’s Court in Lhasa later sentenced him to 15 years prison term in addition to the imposition of fine amounting to 10,000 yuan.

According to another source, Tenchoe’s condition worsened while in prison, as the injuries he sustained in police detention aggravated and he had to make frequent trips to hospitals accompanied by prison guards. Quoting a local eyewitness, the source said, “Tenchoe was brought to one of the hospitals with his hands and legs heavily shackled. He was almost unrecognizable.”

“His physical condition had deteriorated and he had brain injury in addition to vomiting blood.”

Tenzin Choedak, son of Khedup and Passang, was born in October 1981 at Gyabum Gang village in northern part of Lhasa in Tibet Autonomous Region. In 1990, he escaped to India and studied at the Upper Tibetan Children’s Village school in Dharamsala in northern India. He studied up to 10 standard at the school and in 2005 returned to Lhasa. Upon his return to Tibet, he joined a European NGO affiliated to the Red Cross and worked on environmental protection projects in Lhasa and Shigatse.

In the People’s Republic of China, prisoners are often subjected to physical punishments, torture and cruel, inhumane, and degrading treatment. In recent years, the Chinese authorities have adopted the practice of releasing prisoners early so that they do not die in prison. These actions are in complete violation of the United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (SMR) which is a set of rules that outline good principles and practices for the treatment of prisoners and management of prison facilities and prohibit the use of physical punishments and all forms of cruel, inhumane, or degrading treatment. Months before the meeting of the Intergovernmental Expert Group on the SMR in January 2014 to consider proposed changes to SMR, the Chinese government opposed to requiring investigations of deaths that occur shortly after a prisoner is released. China understood that including such a requirement would require the PRC to explicitly refuse to follow the rules or require the PRC to investigate the widespread mistreatment of prisoners that it refuses to acknowledge and attempts to hide from the world. The proposed revisions to SMR require deaths during detention or soon after of a prisoner are investigated by an impartial body to ensure that the deaths were not caused by prison officials. The January 2014 meeting of the Intergovernmental Expert Group on the SMR in Brazil was postponed indefinitely owing to political turmoil in the host country.

TCHRD condemns in the strongest terms the growing number of death in detention cases in Tibet and the failure of accountability on the part of the Chinese authorities to investigate these unnatural deaths. The People’s Republic of China was one of the first member states of the UN to sign the Convention Against Torture in 1986 and ratified in 1988. In the Convention Against Torture, torture is universally prohibited. There are no circumstances that rationalize the existence of torture. Article 2,paragraph 2 of the Convention states: “[n]o exceptional circumstances whatsoever, whether a state of war or a threat of war, internal political instability or any other public emergency, may be invoked as a justification of torture.”

Despite signing and ratifying the Convention, the PRC does not recognize the Committee Against Torture, which is responsible for ensuring the overall implementation of the rights granted by the Convention. Under article 20 of the Convention, the Committee Against Torture has authority to investigate allegations of torture. By taking a reservation to article 20 of the Convention, China demonstrates the utter lack of accountability, thus showing irresponsibility as a member of the international community.

“The death of Tibetan prisoners resulting from their treatment in detention shows efforts by prison authorities to cover up the deaths by releasing the prisoners, thus contributing to a culture of impunity where torture is allowed to flourish,” said Tsering Tsomo, the executive director of TCHRD.