Discriminatory Chinese passport regulations violate Tibetans’ right to travel

Since 2012, Tibetans from the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) have had their passports confiscated and, as a result, unable to travel abroad. This is because of 29 April 2012 ‘guiding opinions’ on implementing passport regulation issued by the Chinese authorities that was recently obtained by the Tibetan Centre for Human Rights and Democracy. The letter of the law and its implementation have prevented almost all Tibetans in the TAR from travelling outside of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). In 2014, further restrictions have prevented Tibetans from travelling to religious ceremonies and sacred sites.

Since 2012, Tibetans from the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) have had their passports confiscated and, as a result, unable to travel abroad. This is because of 29 April 2012 ‘guiding opinions’ on implementing passport regulation issued by the Chinese authorities that was recently obtained by the Tibetan Centre for Human Rights and Democracy. The letter of the law and its implementation have prevented almost all Tibetans in the TAR from travelling outside of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). In 2014, further restrictions have prevented Tibetans from travelling to religious ceremonies and sacred sites.

Article 12(2) of the ICCPR, which is binding on the PRC as part of customary international law, recognizes that everyone has the right to freedom of movement, including the right leave their country. The Human Rights Committee’s General Comment 27 is an authoritative interpretation of this right. It states that international travel cannot be restricted because of the purpose or duration of the travel. The right to freedom of movement may only be restricted in exceptional circumstances when the restriction is necessary to protect national security, public order, public health or morals and the rights and freedoms of others. The General Comment highlighted administrative barriers to travel as a major concern.

The “guiding opinions” issued by the Secretariat Office of TAR Party Committee with copies sent to Political Department of TAR Military and Air Force Command Post of TAR Party Committee, Lhasa, impose substantial restrictions on the ability of Tibetans to obtain passports, which are necessary for international travel. The first section of the document requires that all passports, even those that are still valid, be withdrawn. People can only obtain a new electronic passport after “strict investigation”. The strict investigation involves each application for a new passport to be reviewed 10 times. After delivering the application to the local Public Security Bureau (PSB), the application is reviewed by PSBs at the county, township, prefecture, and regional level. In some cases, the application is reviewed once by the local PSB office in charge of travel and then again by the head of the office. Governments at the village, county, prefecture, and regional level must also review the application. Tellingly, the document only lists the multiple necessary reviews but does not say when a person will receive a passport. It also does not provide any time limit for how long the process should take or mention any right to appeal if a passport application is denied.

People who are given a passport must sign a contract promising not to harm the PRC’s security or interests. Additionally, involvement in any criminal acts will result in the passport being revoked. Article 7 of the Criminal Law of the PRC states that the PRC’s criminal law applies to citizens who are outside of the PRC. The broad references to the PRC’s security and interests and the PRC’s criminal law, which particularly with state secrecy and incitement is notoriously vague, violate the right to travel. It imposes restrictions on the right to travel that violate other protected human rights, for instance, freedom of expression or freedom of assembly if somebody criticise the PRC or attends a prohibited event like a protest or religious service. Article 12(3) of the ICCPR expressly prohibits restrictions on the right to travel that are inconsistent with other rights.

However, invoking Chinese law to justify withdrawing a person’s passport is redundant in light of the document. Part 3 of the “guiding opinions” require that all people who return from travel abroad must within seven days of their arrival give their passports back to the authorities that issued them. PSB officials in charge of travel must also question them. The document does not say when or how a person may get their passport back, how long the questioning will last, or what topics it will cover.

The existing passport regulations along with the “guiding opinions” violate the right to travel internationally. Revoking all passports and making people apply for new passports to severely restrict their ability to travel is not necessary to fulfilling any government objective. The PRC could have accomplished the same administrative task of introducing electronic passports by waiting for old versions to expire and issuing electronic passports when people apply for new passports. This would have been easier for people hoping to travel abroad and the authorities in charge of issuing new passports would not be required to process additional applications. Additionally, Tibetans in Nepal were required to give up their passports. As a result, they were unable to return to Tibet or leave Nepal until they received a new passport.

The “strict investigation” of passport applications also violates the right to travel. Even though it is not mentioned in the document, this language creates a presumption that passports should be difficult to obtain. For officials who want to travel abroad for personal reasons, the document states that in principle officials should not be given passports for personal travel, except in extraordinary circumstances. The multiple levels of review for passport applications create administrative barriers that undermine the right to travel. By requiring that passports be returned within seven days of returning from travel, and presumably making people apply to get their passports returned, creates additional barriers before every international trip. These barriers do not exist for Chinese nationals who apply for passports. In practice, the strict investigations and the bureaucratic barriers prevent Tibetans from receiving passports. For over a year after this document was issued, no Tibetans received passports for non-official travel. This includes Tibetans who were accepted to study in Japan and the United States.

The result of the 2012 “guiding opinions” on implementing the passport regulation was to prevent Tibetans in the TAR from travelling across international borders. This was only the first step in constricting Tibetan’s right to travel. Since 2012, Tibetans have been prevented from travelling to “border areas” for religious purposes, and in some cases, such as in Diru (Ch: Biru) County, Tibetans have been prevented from travelling outside their village. All of these restrictions violate Tibetan’s right to travel. That the violation of human rights is provided for by regulations demonstrates the PRC’s commitment to step away from the rule of law.

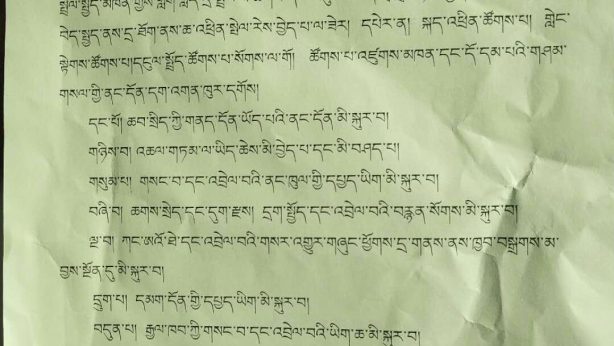

Note: TCHRD has translated the original Chinese language copy of the aforementioned document in Tibetan and English. If you want a copy, email office@tchrd.org with the subject headline “2012 TAR Passport Regulation”.