Extrajudicial detention still a major issue despite RTL abolition

When the National People’s Congress Standing Committee announced the abolition of RTL, it stated that it was because changes made to Chinese laws had made RTL redundant and it had fulfilled its historic mission. This justification fails to recognize the fundamental problems inherent in RTL. It ignores the substantial criticism of RTL for being an illegal system of arbitrary detention, forced labor, and torture. Internationally, numerous States, NGOs, and international organizations, including the United Nations criticized RTL for violating international human rights law. Domestically, Chinese legal scholars criticized RTL as illegal under the PRC’s constitution and in 2012, 87% of Chinese citizens supported abolishing RTL. Thus, when the PRC announces that RTL has fulfilled its historic mission one is forced to wonder what that mission was and whether it was a mission worth completing.

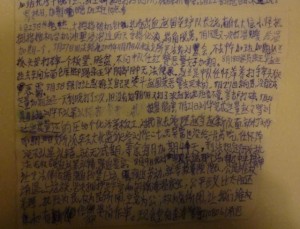

In Tibet, RTL has been used as a tool in the PRC’s crackdown against all non-government supported forms of expression and dissent. Employing tactics uses against Uyghurs, the PRC has sentenced Tibetans to RTL for associating with somebody who receives a long criminal sentence. Lately, this tactic has been used against people who allegedly had some connections to self-immolators. On 1 September 2012, sixty vehicles full of armed police officers stormed the Nyatso Zilkar Monastery in Dzatoe (Ch: Zaduo) town in Tridu (Ch: Chenduo) County in Kyegudo (Ch: Yushu) Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Qinghai Province and arrested five monks. After months of secret detention, Tsultrim Kalsang was sentenced to 10 years in prison for “intentional homicide.” Six other monks Tenzin Sherab, Lobsang Nyima, Sonam Gewa and Lobsang Samten, Sonam Sherab and Sonam Yignyen, were sentenced to two years of RTL. Except for Sonam Sherab, all six were released in July this year. Sonam Yignyen was released prematurely due to failing health; he had spent major portion of his RTL sentence in extreme health condition. Sonam Sherab was held for more months until his release on 23 December 2013. However, there is no information on the release of many others who continue to remain in many known and unknown RTL facilities.

Not only does the PRC not recognize that RTL is a flawed system that violates basic human rights, it seems committed to preserving the abuses related to RTL in other forms. One of the most troubling aspects of the abolition of RTL is the statement that RTL became redundant. It appears that the PRC intends to merely replace RTL with other forms of arbitrary detention, such as compulsory drug rehabilitation and compulsory legal education classes. These systems are already used in Tibet and merely continue the abuses associated with RTL under a different name. In future, Tibetans like Ngawang Topden, who was sentenced to two years of RTL in February 2013 for having photos of friends who committed self-immolation protests on his phone, may be sentenced to drug rehabilitation or legal education instead of RTL. Unfortunately, the treatment is unlikely to change.

If the PRC is going to truly and meaningfully implement reforms it must abolish RTL both in name and practice. This requires abolishing all forms of extrajudicial detention and not merely relabeling it to placate international and domestic critics.