[GUEST POST] The past in the way of the present: Ruminations on Pema Tseten’s movie Old Dog

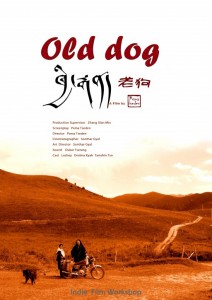

The Tibetan Centre for Human Rights and Democracy (TCHRD) presents one of the most comprehensive and insightful reviews ever done on the critically acclaimed Tibetan feature film Khyi rgan (“Old Dog”), written and directed by Pema Tseten.

Old Dog was screened and discussed at TCHRD’s annual human rights symposium early this year.

In this guest post, scholar and historian Roberto Vitali ruminates on the film’s varied messages along side the tragedy that continues to unfold in the lives and landscapes of the Tibetan plateau under the Chinese, whose “presence are never mentioned” in the film but stays “thick on screen”. Vitali contends that Khyi rgan moves away from the usual anthropological approach to anything Tibetan, avoiding “explanations and erudite posturings” inherent to the anthropological genre. In one of the greatest tributes to Khyi rgyan’s creator, Vitali writes that no one, be it Tibetan or non-Tibetan, has so stunningly depicted Tibet’s tragedy for the Tibetan cinema as Pema Tseten does.

Roberto Vitali is an independent researcher on Tibetan history and literature, and is “deeply taken by [Tibetan] people’s struggle for freedom.” In his own words, Vitali is “like the one in Pema Tseten’s movie, an old dog, who thinks no Chinese will buy him out.”

The past in the way of the present:

Ruminations on Pema Tseten’s movie Old Dog

by Roberto Vitali

Life is an ordeal in societies that put barriers in the way of a smooth and spontaneous flow of social, religious or political forms of expression. When movies are not shot for the sake of mere entertainment but aim at communicating aspects of the reality the creators themselves are steeped in, the result is that cinema of societies threatened by these evils offers food for thought hardly matched by any other. This is perhaps why Third World cinema often yields a much better sense of the heroic than what comes out of productions from bourgeois Western societies.

Having read what people and critics had to say about it, I had long wished to see Pema Tseten’s film Khyi rgan (“Old Dog”). For one reason or another, I never got around to doing so until November 2012. My ruminations on the movie, written at that time, are late in coming, and so I begin with apologies to anyone who dares wasting time to read these lines. I may have been the last man standing in line to view Old Dog. My long expectation was worthy of the days, weeks and years I spent wondering whether I could see it. It all paid off. This movie is the best production ever on Tibet―whether shot by a Tibetan or an Inji―although I have not watched every Tibetan film to hit the silver screen.

~ The director surely has command of filmic language. He knows how to narrate a story and to visualise it. His talent helps the simplicity of the story to unfold in all its beauty and with a strength met with in a cinematic season that is long gone but that was one of the greatest periods of the medium, Italian Neo-Realism, when a powerful mix of filmic narrative skills were put to work on stories that are deeply true. The tragedy of Tibet has never been depicted in such stunning terms as in Old Dog, for Tibetan cinema―whether by Tibetans or Injis―has up till now been somewhat stereotyped by efforts to inject interpretative tip-offs into the subjects chosen. Tibetan film-making is in its infancy, and as with many other disciplines, people from the plateau have just began to expose themselves to it. Old Dog does not aim at illustrating a theme or provide insight into the Tibetan way of life and its people, unlike anthropological movies—the obligatory genre when dealing with anything concerning the plateau. The decision to tell the story that Old Dog tells is what sets it apart. The movie breaks through the deadlock of cinematic works based on the anthropological approach. It is anthropological on many counts, but it is more than that. It is a fictional movie with a poignant theme and deep, multiple messages. In Old Dog Pema Tseten has the great merit to tell a story for what it is, without explanations or erudite posturing. It’s a story that unfolds on the screen at a slow pace. As in some movies of another cinematic genre―the spaghetti westerns―a gradual onset leads to a climax. Movies can transport the viewer to another dimension if they have a good ending. Pema Tseten indeed knows how to handle the dramatic end of his story, a metaphor of Tibetan life on the plateau under the Chinese. The Chinese are never mentioned, but their presence is thick on screen.

~ Khyi rgan tells the story of an old nomad who retrieves his mastiff, the guard of his sheep for many years, from the Chinese man to whom his own son has sold the animal. The son sells it because he realised that doing so is preferable to having it stolen from people involved in the trade of mastiffs to satisfy the demand of affluent Chinese who have recently taken a fancy to the animals. The old nomad gets on his horse and goes downtown to return the money to the Chinese dog merchant and gets his companion back. This is the beginning of a number of attempts by middlemen involved in the trade, lured by the high prices these dogs are fetching from the Chinese, to deprive the old nomad of his sheep guard. Life becomes a sort of nightmare for the old man, who finds himself overcome by the greed of these people. He eventually resorts to the extreme act of killing his own dog rather than seeing him snatched away by thieves.

~ Parallel narratives. There are several narratives that run parallel to the main theme of the old man and his dog. They mainly concern the old man’s son, the major character after the father and his dog. He is the one who sells the dog, but soon after, having witnessed the reaction of his father, he realises that he has made a mistake. His story becomes one of catharsis, leading to his beating up and sending to hospital the Chinese dog merchant who had tried to steal the dog after returning him to the father. The son is portrayed as a confused youth, torn between the beauty of the pastoral life which he reckons as genuine and the leisure of modern existence, being prone to drinking.

There is something that unites the old and the young in the family, and that is television, which exercises an irresistible spell on both of them. They sit together for the ritual of watching it, but with little enthusiasm for the Chinese commercials the TV blasts out without mercy, an example of the vacuity of the new lifestyle that Pema Tseten does not neglect to turn his camera on.

Another parallel theme is the father’s obsessive concern that his son, whom he does not hesitate to brand as useless on every possible occasion, does not yet have a child from his wife. For all the father’s being outraged that he does not care for the continuation of the family, a typical concern of Tibetan collective psyche, the son, being modern, does not feel any compulsion to beget one. Eventually, the father obliges the son to go to hospital and have a medical checkup, which the son feels shameful to have. He obliges his wife to undertake it and comes to know that it is he who is sterile. His pride is hurt, torn between an old-style ego, distressed at a failure that a man should never have to admit to, and the proclivity to avoid responsibility in life. The theme strikes one as a bit forced within the account and is treated rather superficially, as just another contradiction between traditional and modern life.

~ The movie is a case of cultural euthanasia. Faced with the middlemen’s perpetual attempts at stealing his animal or buying him out that are upsetting his own way of life, which will oblige the animal to live in conditions it is not fit for, the old man is left with only one rational choice, killing his dog of thirteen years. The audience gasped in shock and horror in the movie hall during the projection of Old Dog at a Tibetan film festival when the old man suddenly strangles the dog with his chain. I myself was not taken by surprise (I later found out I was not the only one in the room). I had expected something similar to happen. For some time before the climax I was mumbling to myself that the way out of the impasse for the old man had to be drastic―dramatic perhaps―if he were to avoid the continuous risk of losing his companion to others. He decided to lose it to himself, and to let no one else decide in his place that he had to lose it.

~ The moral of the story is that one should “act like a karma yogin”. Once cornered in a situation he does not like and cannot escape, the old man resorts to keeping destiny in his own hands rather than letting it slip out of his control.

~ It’s a story of renunciation. The old man chooses renunciation as a way to free himself from the shackles of a world he does not belong to. It’s a message that sacrificing something one cares for (such as a companion of thirteen years) is a way to move on, and this is what he does after killing his dog. He crosses an empty field into the future―the unknown―with the confidence that he is still himself, and strong in his conviction that he has not sold out to values that are not his own. His world is in tatters but, despite all that has been going wrong, his own world is still intact deep inside him.

~ In many ways, the Chinese arrogate decisions to themselves without leaving any leeway to the Tibetans. Self-immolation and the strangulation of the dog are typical of the few remaining acts Tibetans still have at their command to decide upon themselves. The many cases of self-immolation leave the Chinese unprepared to deal with despite their might; the death of the dog leaves audiences unprepared. Once again Tibetans prove able at least to unsettle the policies of the Chinese and the imagination of audiences around the world. I still wonder whether anyone can explain the Tibetan psyche, which itself is guarded by the ghost of a mastiff.

~ The film ends on a positive note. A renunciation leads to a new beginning. It’s not the son but the old man who walks on across an empty field at the end of the movie after killing his dog. His journey in life is not over.

~ The future is assigned to the old man rather than his son. This is another message; it states that the Tibetan past is the key to its future.

~ Tibet is not for sale. Unlike what is happening in most countries in this age of widespread and rampant pursuit of material gain, including in the Third World, Buddhist ethics being deeply rooted among most people of Tibet, especially―I would dare to say―among the commoners, the craving for money and a wealthy lifestyle is not a priority. Money―in particular, Chinese money to which Tibetans are perforce exposed―cannot buy the Tibetan soul. Old Dog shows that while there are Tibetans in sufficient numbers who are lured by money and easy-earned profit, even implying that this could be what the future holds, it also shows us that those who treasure the values proper to the people of the plateau and their belief system are walking in the opposite direction. They are on a path on which money is not everything; indeed other values come way ahead of it. Economics versus ethics is one more form the battle of spirits takes on the plateau. It can be once again old versus new, but with a difference. The rather detached attitude of commoners in Tibetan society may also rest on a vision that has brought the Chinese eradication of feudalism in Tibet, where the high ranks in the monastic hierarchy had, throughout the century, shown a good amount of attachment to a prosperous and comfortable life. The commoners, who historically had none of that, seem to me to be no less spiritual than a good number of spiritual masters. That the Chinese cannot buy the Tibetan soul with their renminbi spells hope for the future. Improved living conditions (“panem et circenses”), although appealing to almost everyone, are no guarantee that the Chinese can win over a populace who confronts them with utter defiance. I wonder how effective are the rewards promised by the Chinese to anyone who provides information on planned self-immolation. Chinese are gaining no ground with such methods.

~ It’s a story told by means of animals as well. The director seems to have a fair idea of animal husbandry. The brief scene of the isolated sheep that has strayed away from the herd and is seen struggling to reunite with the others beyond a fence is a vivid display of ovine psychology. Indeed fences have been made to divide the land into the plots for the nomads. The fence and sheep are symbols of the divisive land allocation policy adopted by the Chinese. In bygone days nomadic land was not divided up, and never fenced off, and this new practice has increasingly spawned land disputes among Tibetans. Litigiousness hardly serves the purpose of Tibetan identity and does not bode well for the struggle to achieve a better—i.e. independent—future.

The episode is also a symbol of the Tibetan struggle against its imposed isolation, a metaphor of the ideological, economic and humanitarian barriers the Chinese have been building around the plateau. The sheep, isolated from the rest of the herd by the fence, but striving hard to rejoin it by trying every possible passage through the wire mesh and eventually succeeds in finding a hole big enough to go through, is a parable of Tibetan resilience that will be eventually rewarded with freedom.

~ The stillness of time. I have heard complaints that the pace of the movie is slow. Those who say so have probably not experienced the way time flows on the Tibetan plateau, away from the towns that have been transformed into the monstrosities of Chinese steel and mirror. The sandy plains and the hills lit by the sun seem timeless. Life flows with a rhythm of its own, and everyone and everything―men, animals, and even the fierce winds―appear to submit to it. The slowness in the alternation from days to nights is tangibly impressed upon the villages, which have retained very little Tibetanness except for a mockery of traditional architecture. Time there, too, flows slowly, like the mythical water courses of Indo-Tibetan tradition, and unlike the rivers that cross the plateau, making their way turbulently through deserts, rocky terrain and grasslands.

~ The horror of the Chinese insertion into the Tibetan landscape. The Chinese have reduced all villages in Tibet to ugly anonymities. The Amdo village that serves as the scene of several sequences of Old Dog has not escaped this ubiquitous and insensitive fate. It could be any village anywhere in Eastern Tibet. The houses are sinister representatives of a mockery of the old Tibetan architectural tradition. A dusty snooker table stands crippled in the middle of the single road through the village. Small dismal Chinese-style shops packed with cheap basic goods are being run by absent people sitting in them―or outside―with expressionless faces. Everywhere there is mud, spilled machine oil, and noisy, pollutant tractors puffing along the way. The poverty is only heightened by the brutality of the local conditions, an environment of degradation. Pema Tseten sends this other message: the hopelessness of the myriad villages of Tibet and their lost identity and personality. This desolation documents well the Chinese insertion into the Tibetan landscape. In one sense what Pema Tseten shows is meaningful. It points up the alienness and absurdity of this occupation. The ecological damage is massive even on the micro scale, to match the damage created by the great Chinese enterprises, whether through mining or deforestation. Even the weather is gloomy in Pema Tseten’s village, but the sun shines on the pastures where the old man’s sheep graze.

~ The absence of a trace of religion. Liberating. In the movie religion does not exclusively represent and guarantee the spontaneous unfolding of Tibetan culture. Other aspects of Tibetan culture are no less indispensable for the survival of its civilisation. Despite the idea common in occupied Tibet that religion is the lever that will heave freedom, local cultures and traditions also nurture freedom and well-being, insofar as they oppose the oppression of modernity and arrogance.

~ The dogs in the movie. The mastiffs I have seen in Tibet are much wilder than the dogs of the movie. Forget the old dog; even the others look like mascots scampering along on a leash and keeping pace with the battered motorbikes that the actors ride in the movie. The mastiffs I have seen fly like arrows across the plains where nomads pitch their blacks tents.

~ Politics sometimes jeopardises creativity. Nothing against politics―there is much need for it―but the ideological deadlock in the diaspora is so prominent that it has had a sclerotic effect on everything, including Tibetan creativity. In its apparently non-political outlook, a movie from Tibet like Old Dog is subtly and powerfully political. Besides showing the horrors of the Chinese occupation in daily life, it slips in a stark political message, and does it in a way that is poignantly poetical. Paradoxically, a movie director is freer in occupied Tibet, if only he is able to use his creativity, than in exile, where there is an unwritten code requiring adherence to received opinion concerning religion, politics or social realities.

~ It’s a parable of the arrogance and stupidity of a world emptied of its values: the fancy for Tibetan mastiffs that has recently been spreading among affluent urban Chinese is undermining with its greed and opportunism a world established on deep and archaic customs.

~ Khyi rgan is humanistic cinema. It breathes new life into a Tibetan cinema still in its infancy, for it does not want to show or represent something merely entertaining to the audience, but plunges straight into the depths of the Tibetan psyche and transmits to the viewer a sense of anguish that is individual and, for this reason, dramatically collective.

The movie is humanistic in that it documents and offers a description of how changes in culture affect people. It is a movie about change. Change can obviously be either positive or negative. When it comes to Tibet, recent changes have typically been negative, with people’s existences undergoing upheaval through the repression that the Chinese exercise upon every aspect of the traditional way of life. Change is not for the better for the great majority of people in Tibet. The old customs that have forged Tibet into its uniqueness are what the Chinese have been most intent on wiping out. Change is the policy of the occupants. The Tibetans who buy or steal mastiffs are portrayed in the movie as persons motivated by personal financial gain. The movie does not dig further into what may have led them to this new lucrative trade, but their motivation is sheer profit. Profit-seeking is portrayed by Pema Tseten with a cool eye, without any need to pass judgment one way or the other in the face of its own most forceful self-indictment, whereas he follows the old man’s struggle to save what is dear to him with obvious empathy.

~ It’s contemporary, for the movie is built around a theme that is nothing if not a new craze spreading out over the plateau; a craze that, once again, has nothing to do with spontaneous cultural expressions. Mastiffs are not pet dogs.

~ In several cases the movie shows Tibetans living a life of cynicism. Life is accepted by a certain number of locals for what it has become and for what the Chinese have to offer them. There is a perceived dichotomy between the people hanging around in the village and those in nomadic settlements, but life flows in its equally repetitive daily round in the village and on the nomadic pastures with a stillness that the Chinese occupation has not overturned. This theme is the subtle link, the meeting point, between past and modernity in the huge expanse of the plateau outside the major inhabited centres.

The movie does not say whether the few people shown in the village, either playing endless snooker games or sitting in small shops packed with goods of Chinese origin, are ex-nomads obliged to live a village life by the economic conditions created by the foreign occupants. They are depicted as living an indolent life, while the author sees the nomads’ life as full and simple, but ultimately rewarding. The urbanized nomads may not have had to face the hideous destiny of those obliged to move into the compounds built by the Chinese, which resemble prison camps more than spontaneous settlements. Even in Pema Tseden’s village people move around like puppets in search of a stage.

~ In its powerfully striking simplicity, the movie sends out a bold message to the Chinese. The movie’s message is much bolder than most overtly politically-oriented documentaries dealing with Tibetan affairs I know of. The subtlety with which the message is conveyed and the fact that the screenplay apparently deals with a subject that is not blatantly political may have contributed to its being screened—however moderately—outside China in movie festivals around the world without too much hindrance. But I wonder whether everything that is shown and told in the movie has gone down well with the authorities charged with keeping an eye on what messages works of art are conveying. And whether anything has been removed. The movie has seemingly suffered no censorship. Is this a sign of a relaxation of Chinese ideological inflexibility, which would be good news indeed, or is it critical blindness?

~ The message the movie sends out to the Chinese is that integration has been next to nil after more than half a century of their presence in Tibet and that their inflexibility creates conditions that ordinary Tibetans find difficult to stomach. The old man walking into the unknown at the end is a symbol of things to come. It suggests that the future of Tibet is undecipherable, and that for all the paths traced out for them by the Chinese the Tibetans will keep on beating out paths of their own, relying on an inner strength that their world infuses into them despite persecution.

~ The movie should be an eye-opener for the Chinese. It somewhat offers solutions without hinting at what form they might take, not even slightly. It tells that things have not worked in the way sanctioned by the occupiers up till now. It quietly suggests that the time has come for a change to the changes in the way of life brought about in successive waves by the Chinese. But the Chinese may not listen: there is no deaf man so deaf as a man who does not want to hear.