Unveiling enforced disappearances through the Tibetan experience – a panel discussion on the International Day of the Victims of Enforced Disappearance

In 2012, China amended its Criminal Procedure Law, introducing a provision in Article 73 that marked an unconventional departure from established legal norms. This provision enabled a practice known as “Residential surveillance at a designated location” (RSDL), which allowed authorities to detain individuals without formal arrest for up to six months. Notably, this detention could occur at a location chosen by the police, circumventing the need for disclosure, due process, and the possibility of judicial review.

This departure from conventional legal procedures raises concerns as it legalises the use of “enforced disappearance.” This practice starkly contrasts China’s obligations under international human rights treaties it had ratified, such as the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination. China has also signed and ratified the Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment and is accountable to other customary international laws.

In blatant acts of crime against humanity, numerous Tibetans have been subjected to enforced disappearance, leaving their whereabouts shrouded in uncertainty for extended periods. Tibetans have been subjected to arbitrary detention, which often paves the way for enforced disappearance, leading to subsequent instances of torture and inhumane treatment under broad and vague allegations of instigating “social instability” or “separatism”.

On this year’s International Day of the Victims of Enforced Disappearances, The Tibetan Centre for Human Rights and Democracy organised a panel discussion featuring former Tibetan political prisoners and human rights researchers. The panel discussion began with the screening of an explanatory video about enforced disappearance, underscoring the challenges and human rights violations faced by Tibetans including educators, monastics, intellectuals, and activists.

This was followed by TCHRD’s executive director Ms Tenzin Dawa’s presentation on the subject of enforced disappearance, in which she highlighted the case of Gedhun Choekyi Nyima, who was abducted by Chinese government agents after being recognised as the 11th Panchen Lama by the 14th Dalai Lama. Ms Dawa elaborated on the concerns expressed by various UN human rights experts and highlighted the unjust imprisonment of writer Dhi Lhaden, singer Lhundrup Drakpa, and teacher Rinchen Kyi.

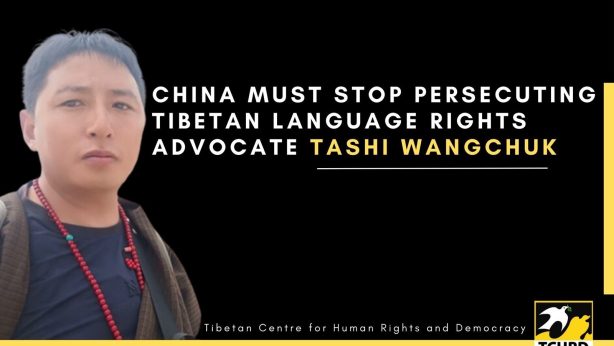

Ms Dawa also referenced the call made by UN Special Rapporteurs to China on 10 August urging the immediate release of nine Tibetan human rights defenders and activists who had been unjustly sentenced to up to 11 years and the joint communication letter sent by six UN independent experts on 26 June 2023 to the Chinese government.

The panel discussion, moderated by TCHRD’s Tibetan researcher Mr Nyiwoe, began with each speaker sharing personal accounts of their experiences as political prisoners.

Mr Gendun Rinchen began by recounting his journey since coming into exile in 1959. He received his education in a Tibetan refugee school in Mussoorie. Following the 1985 Kalachakra initiation by the Dalai Lama, he returned to Tibet, working in Lhasa as a tour guide. Despite China’s attempt to reshape the perceptions of the new Tibetan generation, Gendun Rinchen, as a tour guide, shared information related to human rights issues to tourists and journalists. He was arrested on 13 May 1993 for intending to hand petitions to a visiting European delegation. His detention, lasting eight months, involved three months of intensive interrogation. During his exchanges, he critically questioned the efficacy of Chinese laws that are supposed to safeguard human rights while highlighting the rampant use of enforced disappearance.

Mr Ngawang Woebar was arrested on 27 September 1987. He highlighted the deliberate decision of one participant among the group of 22 protesters to abstain from active engagement, for his task was to secretly observe the authorities’ actions as they transported the arrested individuals. Unfortunately, he was also arrested a month later. The prisoners were forced to make a false confession that the 1987 protest had been orchestrated by the Dalai Lama and the exiled Tibetan government.

Recounting his rigorous interrogation, Woebar mentioned that he was questioned explicitly about a copy of the Dalai Lama’s autobiography, “My Land and My People,” that he had in his possession. Under intense inquiry, he acknowledged that the book discussed Tibetan independence and occupation, prompting immediate orders from the interrogators to refrain from providing further information on the subject matter. The prisoners were beaten and coerced into betraying each other, ultimately facing enforced disappearance.

Former political prisoner Geshe Tsering Dorje, a student of Tulku Tenzin Delek and an advocate for environmental preservation, recounted his experience in Chinese prison as he delved into the stories of various torture methods, including beatings, electrocution and use of needles through fingertips that caused immense pain, bruises and infections due to the highly unhygienic place of detention. He shared how Tibetan political prisoners in Tibet are treated worse than animals by the Chinese authorities.

The discussion concluded with human rights researcher Mr Wangden Kyab, who arrived in exile in 1998. Mr Kyab highlighted China’s continuous violation of its own constitution national laws and its failure to uphold its obligations under international treaties it had signed and ratified.